Patching-up a Ragged Life

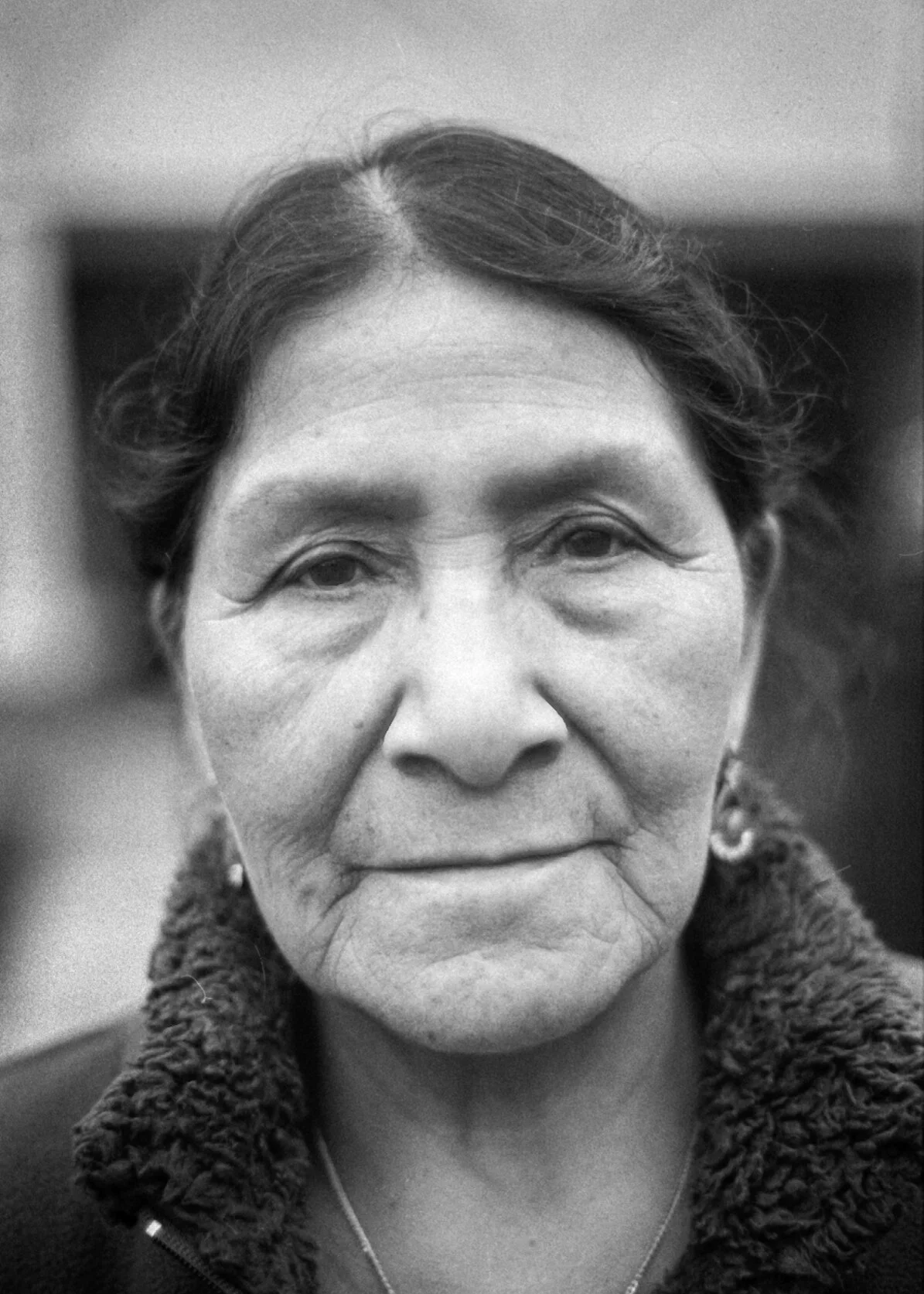

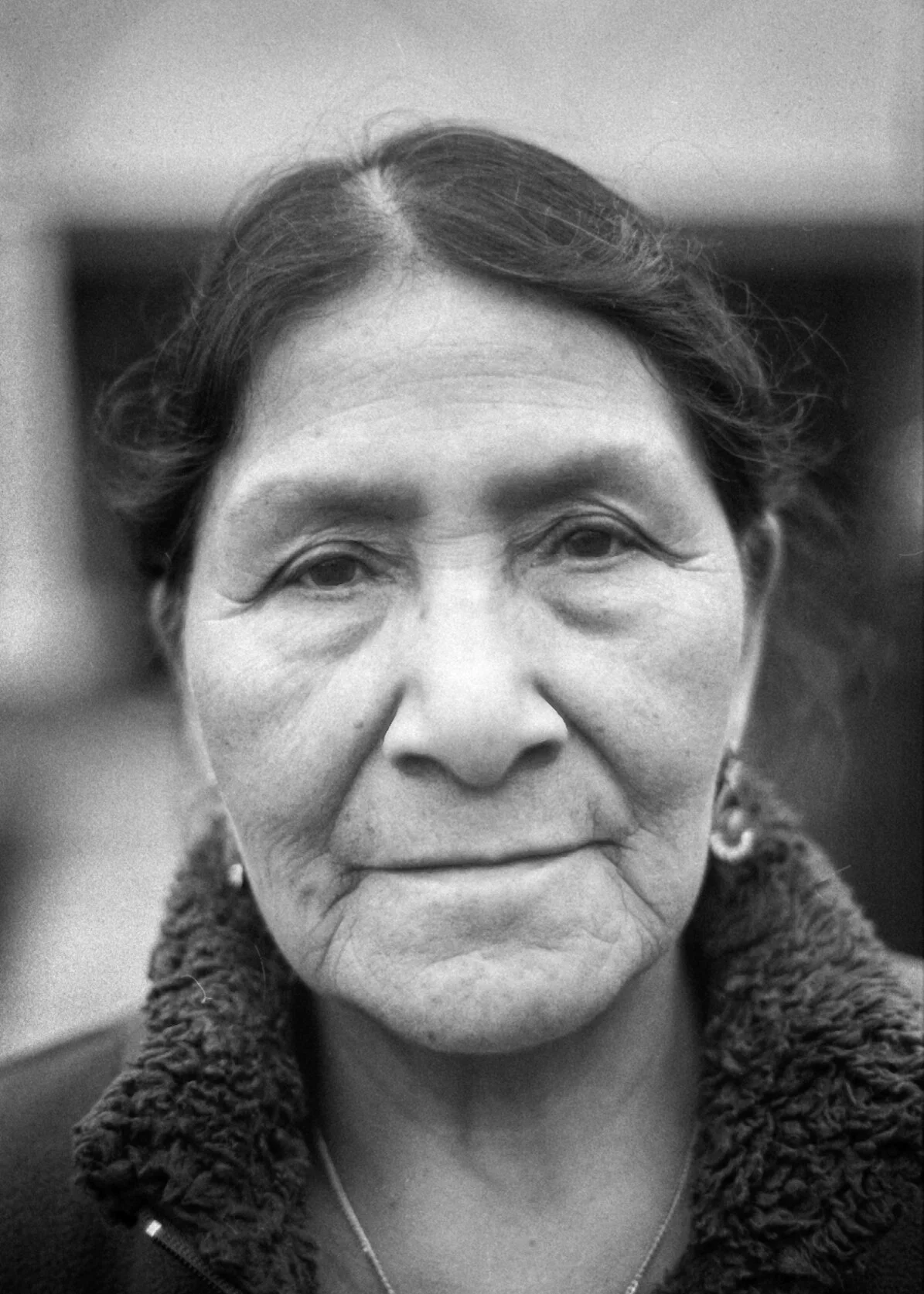

A short documentary of Maria Francisca Guamán Morocho (Mami Pancha) an immigrant with rich Andean heritage who now resides in NC.

Maria Francisca Guamán Morocho known to her vast family as Mami Pancha is an immigrant from Cuenca, Ecuador who resides in Graham, NC. She was born on February 8th, 1946 in what was to become San Jose of Barabon. This village located in a gorge is found right on the outskirts of what is now the city of Cuenca, Ecuador. Both deceased parents (Manuel Jesus Guamán Guanbaña and Maria Cruz Morocho Lima) and their grandparents were illiterate and worked in the hacienda system. Her father would grow up and spend a majority of his life in the hacienda of Miguel Cherres Maldonado and her mother in the hacienda of Los Calderones, which is only a couple of miles west of the Cherres hacienda in the same gorge.

While having the will to dedicate part of their free time to other means of income, her parent’s life revolved around the hacienda system until some change came with the first land reform movement of 1964. The new laws made the hacendados divide the land with those who worked the lands for years. Maria states that her father was called in to see the hacendado one day as rumors arouse that the laws had changed. Her father, Manuel, was scared to go in due to the fear that they might make him sign documents or accuse him being part of a system that was now banned. With fear in his heart he accepted the money the hacendado offered him and left. Mami Pancha says that they should have given him land as they gave to others. It was a quick move from the hacendado to give some money to the Indios (huasinpungeros) in order to retain most of their acquired lands. Mami Pancha’s parents were given 3 to 4 hectares of the worst land on the slope of the gorge to grown crops. They all had schedules and Mami Pancha along with her parents had to work two full days for free in order to have access to the land. She worked for 5 years in this system until she was 18 years old.

In the 1990s, many young men from the villages of the Andean highlands came to the US as undocumented migrants to find the changes they experience to be neither clear-cut nor overwhelmingly positive. They went from stable, if not somewhat fixed, identities as villagers, citizens, husbands, fathers, sons, and brothers to ambiguous subject position as second-class citizens, “illegal aliens,” and disciplined wage laborers. During the 1980s and early 1990s, widespread poverty and the lack of economic opportunities to escape it pushed thousands of individuals out of Azuay and Cañar provinces of Ecuador (Mami Pancha is from the Azuay province) and into low-paying, low-skilled work in the burgeoning service and manufacturing sectors of NY City economy. Migrants thus struggled to piece together elements of their past lives with their new ones in an attempt to order their experiences into a logical and meaningful existence. Because the NY city life offered few resources to reconstruct their previous identities like farmers or village leaders, most men took on different enduring approaches for making their lives meaningful. Of that massive exodus, few were women.

In 1994, Mami Pancha’s daughter, Gloria Guamán Fortner became one of the few women from the conservative south region (Azuayo-Cañari) of Ecuador to migrate into the US with the same mindset as the rest of the men to return to Ecuador after working for 4 or 5 years, once the economic goals have been met, but instead of NY, she ended back in the “south”, in North Carolina. Her decision to leave Ecuador would drastically change Mami Pancha’s life. A single mother, Gloria Gumán Fortner decided to leave for the U.S. leaving her 2-year-old daughter and 1-year-old son with Mami Pancha. At 48 years old Mami Pancha became a mother, again. Her daughter migration became permanent after starting a new family in NC. Sooner than later, the time came for when she had to take the children to their biological mother. In 2005, Mami Pancha found herself in a pena (depression) state after no voices were heard in her old mud house in the gorge. The children she took care of for 11 years were gone. For her everything became silent and the feeling of falta (something missing) that was more like chulla (connoting to something profoundly out of balance).

Mami Pancha’s daughter, Gloria Guamán Fortner, migrated to the US during one of a massive exodus from the southern parts of Ecuador in the late 1980s and early 1990s by borrowing money from shark layers in the city who would come into the rural areas offering to lend money for migrating north. For the same reasons, Mami Pancha dislikes the Cherres hacendados for lending money to the Indians and taking their lands, as they couldn’t repay their debt in time. The Cherres were lawyers and accumulated land throughout the gorge in this manner.

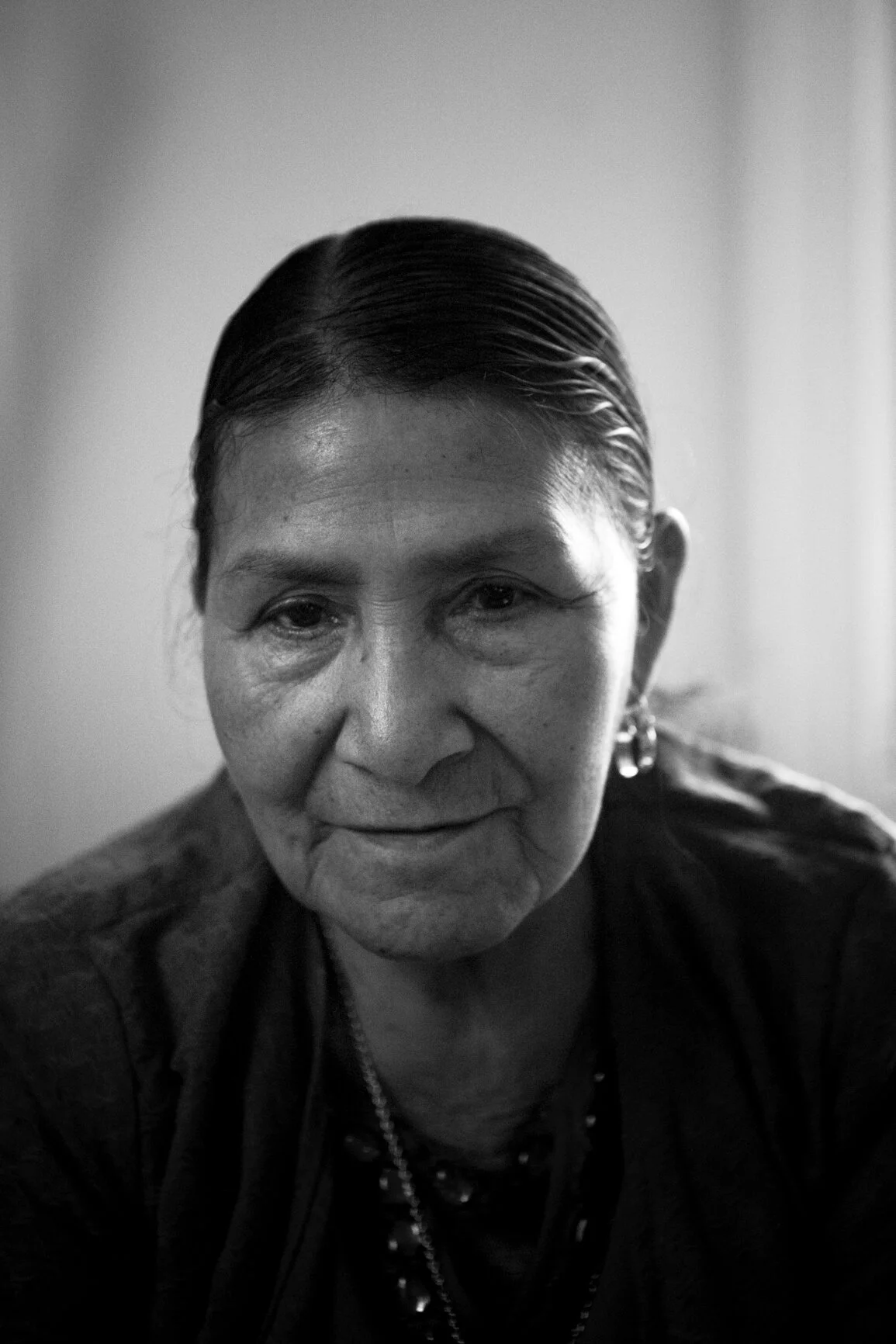

Mami Pancha has many emotional and physical scars from her abusive partner and from the harsh living conditions of the Andes. Since her marriage to Miguel Alejandro Guamán Criollo at the age of 20, Mami Pancha went back to following orders from another person. Her husband emotionally and physically abused her for many years until all of 6 children were of age. Her first baby died a few hours after birth due to no one being there to aide her, not even her husband.

Since she had memory, living in the Andes was also strenuous for Mami Pancha. She had to carry many bricks in the hacienda, hike mountains on daily basis, direct the cattle, weave baskets, wash clothes in the river, walk miles in rain and mud, sleep in the open, work the fields, and carry heavy items like gallons of water, sacks of corn, bundles of grass, firewood, and sacks of potatoes. She is currently facing Arthritis of the knee and is awaiting surgery for sometime at the end of 2019.

“My life hasn’t been a life of freedom. My life has been a life of suffering. Suffering for a better future for my family. I don’t think people would want to listen to this, as my life hasn’t been that of joy. Since I was a little girl, I never had time to play. We were poor and I had to honor thy mother and father. Before sunrise you’d have to be working the lands. We needed to carry water from the river in order to cook and lived/worked without electricity. I tell my daughters in Ecuador that we have everything come to us now.”

“The man gives orders. My mother would tell me that. A woman couldn’t do anything without having a man. A woman without the order given by the man could not drive a car, could not be a lawyer, not even be able to put a yunta (yoke) together. That ideology comes from way back. Women were given orders by the boss and by the husband. Since I was a child I was told to believe this. We couldn’t dance. Nowadays I can go work whenever I want to and even dance whenever I want to. It’s just this leg that bothers me so I can only do much.”

Mami Pancha’s parents were artisans. During their free time they made baskets of (suro) a wild solid think bamboo that grows at higher altitudes in the Andes Mountains. Both parents lived off the land while also weaving baskets and exchanging crops for other needed items like sugar and salt. Mami Pancha father was a shoemaker for a short time with rubber being the material he used. He made her the first pair of shoes she would wear as a present for starting school. By the end of the week someone had cut them in half. She mentions that jealousy made her half brother cut them in half.

To her recollection, Mami Pancha mentions that almost everyone that lived in the gorge knew how to weave baskets, as that is what they were know for. Maria Cruz Morocho Lima not only made baskets, but also resold them in the big market called Rotary. Maria Cruz Morocho Lima had her own official licensed booth through the municipality. Both parents had knowledge of currency and at times traded their baskets for different grains and seeds. Mami Pancha remembers making a two-day travel to Giron by foot to retrieve Yucca and Panela (a solid form of sucrose derived from the boiling and evaporation of sugarcane juice), two food sources that come from the hot coast.

Mami Pancha has 5 daughters and a son. Two of her daughters have a disability and she provides for them. While weaving baskets was her main source of income in Cuenca, Ecuador, she now works at a huge factory in NC called Pratt Display. They are a supplier of sustainably sourced point-of purchase displays. There she works from 7am-3pm. An early riser she often is up making her and her husband’s chinrir (breakfast) by 5am.

Mami Pancha said to have walked from sunrise to sunset as a child when her family had to go sell their baskets and buy house necessities like salt and sugar. Her means of putting food on the table was working the land and weaving two types of baskets (canastas and tazas) from two kinds of South American mountain bamboos. They are called Duda and Suro in the Cañari-Azuayo region. These grow in paramo regions and are brought down to lower rural areas by those who live in higher altitudes. Most of Mami Pancha’s life was dedicated to this way of living and other including the farming of corn, beans, squash, and raising animals like cattle, pigs, sheep, and chickens. Today, some of the women who live in the village own small eateries. This has been a major change in the recent years on how the income is generated.

Mami Pancha works at Pratt Display making boxes. While difficult at first, after working a few years, she has become an expert and shares how she has become a favorite at work due to her work ethic. Putting together boxes and weaving baskets are arduous on the hands. At 73 years old, Mami Pancha finds herself tired once she gets home. Often she enjoys a nap before making dinner. She enjoys cooking, as she has done it her whole life.

“Sometime they fight over me. They want me at their line. I have to walk slowly at work. During my break and when it’s time to leave, I am always last. I have the Virgin Mary on my back looking out for me. She makes sure I don’t take a misstep.”

Just as the Andean and Spanish people came into conflict during colonization, so did their gods. However the local gods did not vanish into oblivion, but remained in other forms, even in some places in their original form. Mami Pancha believes that her ancestors didn’t follow the right religion and that Catholicism saved us. Many throughout the Andes share this belief. Catholicism and Spanish Colonialism have tried to erase their connection to their past and attempt to mold a new narrative. While practicing indigenous traditions and some rituals such as the cleansing of evil energy with herbs among other things, Mami Pancha sees herself as catholic first. People in the Andes practice what some call Andean-Catholicism.

Religion in Mami Pancha’s life is important. If she is to talk about her plans for tomorrow or if she hopes for something, she always starts her sentence with “Si Dios quiere (If God allows it) I will…” If something is given to her, especially material items, she responds with a “Dioslipague (May God repay you),” which has evolve to become a short form of thank you, because the actual full sentence would be “Que Dios le pague.” She prays every morning before taking a step out of bed and before going to sleep at night. It’s a ritual. She attends Catholic mass on Sundays and participates on most church events.

In her payer she never forgets about the Virgin Mary. She is as important as God, his son Jesus, and the Holy Spirit. The Virgin Mary in Andean culture is as important as the holy trinity, if not more. To her there is only one God and that he is divided into God himself, his son, Jesus, and the Holy Spirit but that the Virgin Mary is as important due to being the chosen one as the mother of Jesus.

In Andean culture there is a powerful Goddess called Pachamama who at times is syncretized with the Virgin Mary. She is a fertility goddess who presides over planting and harvesting, embodies the mountains, and causes earthquakes among other forms of punishment to those who abuse of her. What she has given can be taken. Her name can be translated to “Mother Earth.” The inclination towards the Virgin Mary in Andean culture could be due to the respect and adoration Andeans have with the earth. As time passes, Andeans have moved to accept a form of Christianity, but still have a special place for this female figure among other Andean beliefs.

Mami Pancha spent her whole life in Ecuador planting corn, squash, and beans. Two of her daughters and granddaughters still work the fields planting the same crops she grew up on. They have now added onions, carrots, and cabbage to the mix of vegetables they produce. The planting season for the three sisters (corn, squash, and beans) is September. Then you follow those two months later with a deservar (the action of taking the weeds out from around the crops) stage so that the small plant can breath freely. In January you do a segundar stage where you add more dirt around the plant and at times tie it to a pole in preparation for the winds. On May 3rd the harvesting season is at its peak. Andeans paralleled harvesting season with the sighting of the Crux Constellation or Chacana (Andean cross). Andeans used a lunar calendar of 13 months with 28 days each month: 13 by 28 gives 364 days. Day 365 was considered day zero. That day is May 3, when the Southern Cross takes on the astronomical (geometric) form of a perfect Latin cross. Mami Pancha remembers that the whole village would be encouraged to bathe in the freezing river early in the morning on May 3rd. She isn’t clear of why elders made them do it.

Mami Pancha now gets her corn, potatoes, eggs, etc. from ALDI. She wishes she could plant them, herself. She often compares them with those harvested in Ecuador in the past. She worries that the young are forgetting the land.

“Our elders were hardworking people. We grabbed our hoes, shovels, and other planting and cultivating tools. Our people didn’t need to go work in the city. We only lived from agriculture. Nowadays only a few plant crops. Those who are renascent don’t care as much. One can live from the land. The youth doesn’t want to live and endure like past times. They wish to live soothing lives. They don’t want to live from agriculture. In the past our elders had to plant our crops on borrowed land (referring to the hacienda). We have the opportunity to grow our own crops, but it seems like the youth is abandoning this way of life.

Our people never studied. The new generation has to go study in the city. Studying is good, however, we should give a day or even three hours to plating our crops. One has to have afán (eagerness, dedication, effort). When I was in my youth, I would run around from one place to the other. Nowadays I have trouble walking. This leg is bothering me; otherwise I would be able to do more.”

Growing without the aide of technology, Andean civilizations had to acquire certain abilities in order to predict the weather or indicate the time of day. For that and for more they sided aid from nature. Mami Pancha owned hens and rosters in Ecuador. They would let her know when it was 4am, 5am, 6am. She mentions that because of living in a gorge, the sun would always hit the top of the mountain at 6:30am and again at 5:30pm. She has the ability to estimate the time from just looking where the sun is positioned, up to the nearest minute. She is also able to predict if there will be hail or rain the next day just by looking at the pattern and shape of the clouds. If it rained high in the mountains and the river was going to overflow, she would anticipate it by looking at the birds and checking the wood particles in the water.

In the Andes there exists a form of folk healing called curanderismo that includes various techniques such as prayer, herbal medicine, healing rituals, spiritualism, and psychic healing. There are also Yerbateros (Herbalist) or Medico Casero (domestic doctor) as Mami Pancha calls them, which specialize in curing people with herb knowledge that has been passed down from generation to generation. Other special healers are parteras (midwives) and sobadores (those who use massage and acupressure to treat physical aliments).

Curanderismo, by contrast, can be used to treat a wide range of social, spiritual, psychological, and physical problems: Headaches, gastrointestinal problems, back pain, fever, anxiety, irritability, fatigue, depression, mala suerte (bad luck), marital discord, and illnesses caused by susto (fright or soul loss). Treatments typically involve spiritual, emotional, and mental approaches as well as more physical means. Some of the more common causes of illness in the Andes in fact are almost entirely spiritual in nature, such as mal de ojo (the evil eye), susto, and envidia (jealousy) and since medical science cannot treat these it is another reason why a healer rather than a doctor might be sought. In all of the cases above the curandero may perform limpias or barridas (ritual cleansings) to rebalance the body and soul of the sick person. According to Mami Pancha the most affected by susto, mal de ojo, or envidia are newborns including animals.

Mami Pancha is a talkative person, just as most elders are. They didn’t have a form of writing and passed down stories orally from generation to generation. That means that some of the stories would change as they were retold. Mami Pancha often speaks of such myths or leyendas when sitting down with her family. She often tells the myth of the woman who was too ambitious.

“She wanted to marry someone rich who had golden teeth and dressed well. However, all men in the village were poor. She wanted to find the richest man. One day such man came into the village and she fell for him, instantly. Without her parent’s permission, she left with the stranger. They walked for miles over the mountains and finally arrived at the base of a big tree. She was shocked to see that his home was a tree. The man carried her up the tree and one day passed. The next evening she was hungry and asked the man for food. He rushed down the tree and later on came back with a bull carcass. She told him that the meat was uncooked and will not eat it raw. The man sliced a piece and placed it over the lights from a far away city. To him it resembled a fire. She was confused and so hungry that she ate it. Another day passed and she grew puzzled. On the third day she realized that the man was oddly hairier that usual. On the fourth day she came to figure out that the man was actually a bear. Shortly after he went to gather food, she left in a hurry for her village. She found the villagers and her parents and told them everything. She also asked for them to hide her and the bear will come back smelling her scent. Indeed that evening the bear showed up in the entrance of the village. The whole villagers clashed with the bear and one villager sliced his stomach. The bear grabbed the long thick grass and sewed his stomach before running away. The woman and the villagers came out victorious. Sometime later the woman would find herself pregnant and would give birth to a bear-child with massive strength. His name was Juan del Oso.”

Despite there only being one bear species in South America (the spectacled bear), the story of The Bear’s Wife and Children is a prominent story among the Andean people. This is Mami Panchas version passed down orally by her mother.

Remendando la Llachapa Vida

Un breve documental de María Francisca Guamán Morocho (Mami Pancha), una inmigrante con una rica herencia andina que ahora reside en NC.

María Francisca Guamán Morocho conocida por su vasta familia como Mami Pancha es una inmigrante de Cuenca, Ecuador que reside en Graham, NC. Nació el 8 de febrero de 1946 en lo que sería San José de Barrabón. Este pueblo ubicado en una quebrada se encuentra justo en las afueras de lo que hoy es la ciudad de Cuenca, Ecuador. Ambos padres fallecidos (Manuel Jesús Guamán Guanbaña y María Cruz Morocho Lima) y sus abuelos eran analfabetos y trabajaban en el sistema de haciendas. Su padre crecería y pasaría la mayor parte de su vida en la hacienda de Miguel Cherres Maldonado y su madre en la hacienda de Los Calderones, que está a solo un par de millas al oeste de la hacienda de Cherres en el mismo desfiladero.

Si bien tenía la voluntad de dedicar parte de su tiempo libre a otros medios de ingresos, la vida de sus padres giró en torno al sistema de hacienda hasta que llegó un cambio con el primer movimiento de reforma agraria de 1964. Las nuevas leyes hicieron que los hacendados dividieran la tierra con los que trabajaron las tierras durante años. María afirma que un día llamaron a su padre para que viera al hacendado cuando surgieron rumores de que las leyes habían cambiado. Su padre, Manuel, tenía miedo de entrar por temor a que lo hicieran firmar documentos o lo acusaran de ser parte de un sistema que ahora estaba prohibido. Con temor en el corazón aceptó el dinero que le ofreció el hacendado y se fue. Mami Pancha dice que le debieron dar tierra como le dieron a otros. Fue un movimiento rápido del hacendado dar algo de dinero a los indios (huasinpungeros) para retener la mayor parte de sus tierras adquiridas. A los padres de Mami Pancha les dieron de 3 a 4 hectáreas de la peor tierra en la ladera de la quebrada para sembrar cultivos. Todos tenían horarios y Mami Pancha junto con sus padres tenían que trabajar dos días completos gratis para tener acceso a la tierra. Trabajó durante 5 años en este sistema hasta los 18 años.

En la década de 1990, muchos hombres jóvenes de las comunidades de las tierras altas de los Andes llegaron a los EE. UU. como inmigrantes indocumentados y descubrieron que los cambios que experimentaban no eran claros ni abrumadoramente positivos. Pasaron de identidades estables, si no algo fijas, como comuneros, ciudadanos, esposos, padres, hijos y hermanos a una ambigua posición de sujeto como ciudadanos de segunda clase, "extranjeros ilegales" y trabajadores asalariados disciplinados. Durante la década de 1980 y principios de la de 1990, la pobreza generalizada y la falta de oportunidades económicas para escapar de ella empujó a miles de personas de las provincias de Azuay y Cañar de Ecuador (Mami Pancha es de la provincia de Azuay) a trabajos mal remunerados y poco calificados en los florecientes sectores de servicios y manufactura de la economía de la ciudad de Nueva York. Por lo tanto, los migrantes lucharon por juntar elementos de sus vidas pasadas con las nuevas en un intento de ordenar sus experiencias en una existencia lógica y significativa. Debido a que la vida de la ciudad de Nueva York ofrecía pocos recursos para reconstruir sus identidades anteriores como agricultores o líderes de aldeas, la mayoría de los hombres adoptaron diferentes enfoques duraderos para hacer que sus vidas tuvieran sentido. De ese éxodo masivo, pocas eran mujeres.

En 1994, la hija de Mami Pancha, Gloria Guamán Fortner, se convirtió en una de las pocas mujeres de la conservadora región sur (Azuayo-Cañari) de Ecuador en migrar a los EE. UU. con la misma mentalidad que el resto de los hombres en regresar a Ecuador después de trabajar para 4 o 5 años, una vez cumplidas las metas económicas, pero en lugar de NY, terminó de regreso en el “sur”, en Carolina del Norte. Su decisión de irse de Ecuador cambiaría drásticamente la vida de Mami Pancha. Gloria Gumán Fortner, una madre soltera, decidió irse a los Estados Unidos dejando a su hija de 2 años y a su hijo de 1 año con Mami Pancha. A los 48 años Mami Pancha volvió a ser madre. La migración de su hija se volvió permanente después de formar una nueva familia en NC. Más temprano que tarde, llegó el momento de llevar a los niños a su madre biológica. En 2005, Mami Pancha se encontró en un estado de pena (depresión) después de que no se escucharan voces en su vieja casa de barro en la quebrada. Los niños que cuidó durante 11 años ya no estaban. Para ella todo se convirtió en silencio y la sensación de falta (algo que falta) que era más como chulla (que connotaba algo profundamente desequilibrado).

La hija de Mami Pancha, Gloria Guamán Fortner, emigró a los EE. UU. durante uno de los éxodos masivos del sur de Ecuador a fines de la década de 1980 y principios de la de 1990 al pedir dinero prestado a los criadores de tiburones en la ciudad que vendrían a las áreas rurales y se ofrecerían a prestar. dinero para emigrar al norte. Por las mismas razones, a Mami Pancha le desagradan los hacendados de Cherres por prestar dinero a los indios y tomar sus tierras, ya que no pudieron pagar su deuda a tiempo. Los Cherre eran abogados y acumularon tierras en todo el desfiladero de esta manera.

Mami Pancha tiene muchas cicatrices emocionales y físicas de su pareja abusiva y de las duras condiciones de vida de los Andes. Desde su matrimonio con Miguel Alejandro Guamán Criollo a los 20 años, Mami Pancha volvió a seguir órdenes de otra persona. Su esposo abusó emocional y físicamente de ella durante muchos años hasta que sus 6 hijos cumplieron la mayoría de edad. Su primer bebé murió pocas horas después del nacimiento debido a que nadie estaba allí para ayudarla, ni siquiera su esposo.

Desde que tiene memoria, vivir en los Andes también fue extenuante para Mami Pancha. Tuvo que acarrear muchos ladrillos en la hacienda, escalar montañas diariamente, dirigir el ganado, tejer canastas, lavar ropa en el río, caminar kilómetros bajo la lluvia y el lodo, dormir a la intemperie, trabajar los campos y cargar objetos pesados como galones de agua, sacos de maíz, manojos de pasto, leña y sacos de papas. Actualmente enfrenta artritis en la rodilla y está a la espera de una cirugía en algún momento a fines de 2019.

“Mi vida no ha sido una vida de libertad. Mi vida ha sido una vida de sufrimiento. Sufrir por un futuro mejor para mi familia. No creo que la gente quiera escuchar esto, ya que mi vida no ha sido de alegría. Desde que era una niña, nunca tuve tiempo para jugar. Éramos pobres y tuve que honrar a tu madre y a tu padre. Antes del amanecer tendrías que estar trabajando las tierras. Necesitábamos llevar agua del río para poder cocinar y vivíamos/trabajábamos sin electricidad. A mis hijas en Ecuador les digo que todo nos llega ahora”.

“El hombre da órdenes. Mi madre me diría eso. Una mujer no podía hacer nada sin tener un hombre. Una mujer sin la orden dada por el hombre no podía conducir un carro, no podía ser abogada, ni siquiera poder armar una yunta. Esa ideología viene de mucho tiempo atrás. Las mujeres recibían órdenes del jefe y del marido. Desde que era niño me dijeron que creyera esto. No podíamos bailar. Hoy en día puedo ir a trabajar cuando quiero e incluso bailar cuando quiero. Es solo esta pierna la que me molesta, así que solo puedo hacer mucho”.

Los padres de Mami Pancha eran artesanos. Durante su tiempo libre, hicieron canastas de (suro) un bambú silvestre sólido que crece en altitudes más altas en las montañas de los Andes. Ambos padres vivían de la tierra mientras también tejían canastas e intercambiaban cultivos por otros artículos necesarios como azúcar y sal. Mami Pancha padre fue zapatero por un corto tiempo siendo el caucho el material que utilizaba. Él le hizo el primer par de zapatos que usaría como regalo para comenzar la escuela. Al final de la semana alguien los había cortado por la mitad. Ella menciona que los celos hicieron que su medio hermano los cortara por la mitad.

Según ella recuerda, Mami Pancha menciona que casi todos los que vivían en la quebrada sabían tejer canastas, pues para eso eran conocidos. María Cruz Morocho Lima no solo hacía canastas, sino que también las revendía en el gran mercado llamado Rotary. María Cruz Morocho Lima tenía su propio stand oficial autorizado a través del municipio. Ambos padres tenían conocimiento de la moneda y en ocasiones cambiaban sus canastas por diferentes granos y semillas. Mami Pancha recuerda haber hecho un viaje de dos días a pie a Girón para recuperar yuca y panela (una forma sólida de sacarosa derivada de la ebullición y evaporación del jugo de caña de azúcar), dos fuentes de alimentos que provienen de la costa caliente.

Mami Pancha tiene 5 hijas y un hijo. Dos de sus hijas tienen una discapacidad y ella las mantiene. Si bien tejer canastas era su principal fuente de ingresos en Cuenca, Ecuador, ahora trabaja en una gran fábrica en Carolina del Norte llamada Pratt Display. Son un proveedor de pantallas de punto de compra de origen sostenible. Allí trabaja de 7 am a 3 pm. Madrugadora, a menudo se levanta y prepara el chinrir (desayuno) para ella y su esposo a las 5 am.

Mami Pancha dijo haber caminado desde el amanecer hasta el atardecer cuando su familia tenía que ir a vender sus canastas y comprar artículos de primera necesidad para la casa como sal y azúcar. Su manera de llevar comida a la mesa era trabajar la tierra y tejer dos tipos de canastas (canastas y tazas) con dos tipos de bambúes de las montañas sudamericanas. Se llaman Duda y Suro en la región Cañari-Azuayo. Estos crecen en las regiones de páramo y son llevados a las zonas rurales más bajas por aquellos que viven en altitudes más altas. La mayor parte de la vida de Mami Pancha se dedicó a esta y otras formas de vida, incluyendo el cultivo de maíz, frijol, calabaza y la crianza de animales como ganado vacuno, porcino, ovino y pollos. Hoy en día, algunas de las mujeres que viven en el pueblo son propietarias de pequeños comedores. Este ha sido un cambio importante en los últimos años sobre cómo se generan los ingresos.

Mami Pancha trabaja en Pratt Display haciendo cajas. Si bien es difícil al principio, después de trabajar unos años, se ha convertido en una experta y comparte cómo se ha convertido en una de sus favoritas en el trabajo debido a su ética de trabajo. Armar cajas y tejer canastas es arduo para las manos. A los 73 años, Mami Pancha se encuentra cansada una vez que llega a casa. A menudo disfruta de una siesta antes de preparar la cena. Le gusta cocinar, ya que lo ha hecho toda su vida.

“A veces se pelean por mí. Me quieren en su línea. Tengo que caminar despacio en el trabajo. Durante mi descanso y cuando es hora de irse, siempre soy el último. Tengo a la Virgen María en mi espalda cuidándome. Ella se asegura de que no dé un paso en falso”.

Así como los andinos y los españoles entraron en conflicto durante la colonización, también lo hicieron sus dioses. Sin embargo, los dioses locales no desaparecieron en el olvido, sino que permanecieron en otras formas, incluso en algunos lugares en su forma original. Mami Pancha cree que sus antepasados no siguieron la religión correcta y que el catolicismo nos salvó. Muchos a lo largo de los Andes comparten esta creencia. El catolicismo y el colonialismo español han tratado de borrar su conexión con su pasado e intentar moldear una nueva narrativa. Mientras practica las tradiciones indígenas y algunos rituales como la limpieza de la energía maligna con hierbas, entre otras cosas, Mami Pancha se ve a sí misma como católica primero. La gente de los Andes practica lo que algunos llaman catolicismo andino.

La religión en la vida de Mami Pancha es importante. Si va a hablar de sus planes para mañana o si espera algo, siempre comienza su frase con “Si Dios quiere (si Dios lo permite) lo haré…” Si se le da algo, especialmente cosas materiales, ella responde con un "Dioslipague (Que Dios te pague)", que ha evolucionado para convertirse en una forma corta de gracias, porque la oración completa real sería "Que Dios le pague". Reza todas las mañanas antes de dar un paso fuera de la cama y antes de irse a dormir por la noche. Es un rito. Asiste a misa católica los domingos y participa en la mayoría de los eventos de la iglesia.

En su pagador nunca se olvida de la Virgen María. Ella es tan importante como Dios, su hijo Jesús y el Espíritu Santo. La Virgen María en la cultura andina es tan importante como la santísima trinidad, si no más. Para ella hay un solo Dios y que se divide en Dios mismo, su hijo Jesús y el Espíritu Santo pero que la Virgen María es tan importante por ser la elegida como la madre de Jesús.

En la cultura andina existe una Diosa poderosa llamada Pachamama que en ocasiones se sincretiza con la Virgen María. Es una diosa de la fertilidad que preside la siembra y la cosecha, encarna las montañas y provoca terremotos entre otras formas de castigo a quienes abusan de ella. Lo que ella ha dado se puede tomar. Su nombre se puede traducir como "Madre Tierra". La inclinación hacia la Virgen María en la cultura andina podría deberse al respeto y adoración que los andinos tienen con la tierra. A medida que pasa el tiempo, los andinos se han movido para aceptar una forma de cristianismo, pero aún tienen un lugar especial para esta figura femenina entre otras creencias andinas.

Mami Pancha pasó toda su vida en Ecuador sembrando maíz, calabaza y frijol. Dos de sus hijas y nietas aún trabajan en los campos sembrando los mismos cultivos en los que ella creció. Ahora han agregado cebollas, zanahorias y repollo a la mezcla de vegetales que producen. La época de siembra de las tres hermanas (maíz, calabaza y frijol) es septiembre. Luego sigue esos dos meses más tarde con una etapa de deservar (la acción de sacar las malas hierbas de alrededor de los cultivos) para que la pequeña planta pueda respirar libremente. En enero, haces una segunda etapa en la que agregas más tierra alrededor de la planta y, en ocasiones, la atas a un poste en preparación para los vientos. El 3 de mayo la temporada de cosecha está en su apogeo. Los andinos compararon la temporada de cosecha con el avistamiento de la Constelación Crux o Chacana (cruz andina). Los andinos usaban un calendario lunar de 13 meses con 28 días cada mes: 13 por 28 da 364 días. El día 365 se consideró el día cero. Ese día es el 3 de mayo, cuando la Cruz del Sur toma la forma astronómica (geométrica) de una cruz latina perfecta. Mami Pancha recuerda que todo el pueblo se animaría a bañarse en el río helado la madrugada del 3 de mayo. Ella no tiene claro por qué los ancianos los obligaron a hacerlo.

Mami Pancha ahora obtiene su maíz, papas, huevos, etc. de ALDI. Ella desea poder plantarlos, ella misma. A menudo las compara con las cosechadas en Ecuador en el pasado. Le preocupa que los jóvenes se estén olvidando de la tierra.

“Nuestros mayores eran gente trabajadora. Agarramos nuestras azadas, palas y otras herramientas para sembrar y cultivar. Nuestra gente no necesitaba ir a trabajar a la ciudad. Sólo vivíamos de la agricultura. Hoy en día sólo unos pocos cultivos de plantas. A los que son renacientes no les importa tanto. Se puede vivir de la tierra. La juventud no quiere vivir y sufrir como en tiempos pasados. Desean vivir una vida tranquila. No quieren vivir de la agricultura. En el pasado nuestros mayores tenían que sembrar nuestras cosechas en terrenos prestados (refiriéndose a la hacienda). Tenemos la oportunidad de cultivar nuestros propios cultivos, pero parece que la juventud está abandonando esta forma de vida.

Nuestra gente nunca estudió. La nueva generación tiene que irse a estudiar a la ciudad. Estudiar es bueno, sin embargo, debemos dedicar un día o hasta tres horas a sembrar nuestras cosechas. Hay que tener afán (afán, dedicación, esfuerzo). Cuando era joven, corría de un lugar a otro. Actualmente tengo problemas para caminar. Esta pierna me está molestando; de lo contrario, podría hacer más”.

Al crecer sin la ayuda de la tecnología, las civilizaciones andinas tuvieron que adquirir ciertas habilidades para predecir el clima o indicar la hora del día. Por eso y por más buscaron la ayuda de la naturaleza. Mami Pancha poseía gallinas y rosters en Ecuador. Le avisaban cuando eran las 4 am, 5 am, 6 am. Ella menciona que por vivir en un desfiladero, el sol siempre llegaba a la cima de la montaña a las 6:30 am y nuevamente a las 5:30 pm. Ella tiene la capacidad de estimar el tiempo con solo mirar dónde se coloca el sol, hasta el minuto más cercano. También es capaz de predecir si habrá granizo o lluvia al día siguiente con solo observar el patrón y la forma de las nubes. Si llovía en lo alto de las montañas y el río iba a desbordarse, lo anticipaba mirando a los pájaros y comprobando las partículas de madera en el agua.

En los Andes existe una forma de curación popular llamada curanderismo que incluye diversas técnicas como la oración, la fitoterapia, los rituales de curación, el espiritismo y la curación psíquica. También están los Yerbateros (herbolario) o Medico Casero (médico doméstico) como los llama Mami Pancha, que se especializan en curar a las personas con conocimientos de hierbas que se han transmitido de generación en generación. Otros curanderos especiales son las parteras (parteras) y los sobadores (aquellos que usan masajes y acupresión para tratar enfermedades físicas).

El curanderismo, por el contrario, se puede utilizar para tratar una amplia gama de problemas sociales, espirituales, psicológicos y físicos: dolores de cabeza, problemas gastrointestinales, dolor de espalda, fiebre, ansiedad, irritabilidad, fatiga, depresión, mala suerte, marital. discordia y enfermedades causadas por susto (susto o pérdida del alma). Los tratamientos suelen implicar enfoques espirituales, emocionales y mentales, así como medios más físicos. De hecho, algunas de las causas más comunes de enfermedad en los Andes son de naturaleza casi completamente espiritual, como el mal de ojo, el susto y la envidia (celos), y dado que la ciencia médica no puede tratarlas, esta es otra razón por la cual se podría buscar un curandero en lugar de un médico. En todos los casos anteriores el curandero puede realizar limpias o barridas (limpiezas rituales) para reequilibrar el cuerpo y el alma del enfermo. Según Mami Pancha, los más afectados por el susto, el mal de ojo o la envidia son los recién nacidos, incluidos los animales.

Mami Pancha es una persona conversadora, como la mayoría de los ancianos. No tenían una forma de escritura y transmitían las historias de forma oral de generación en generación. Eso significa que algunas de las historias cambiarían a medida que se volvieran a contar. Mami Pancha suele hablar de tales mitos o leyendas cuando se sienta con su familia. A menudo cuenta el mito de la mujer demasiado ambiciosa.

“Ella quería casarse con alguien rico que tuviera dientes de oro y vistiera bien. Sin embargo, todos los hombres del pueblo eran pobres. Quería encontrar al hombre más rico. Un día, un hombre así llegó al pueblo y ella se enamoró de él al instante. Sin el permiso de sus padres, se fue con el extraño. Caminaron por millas sobre las montañas y finalmente llegaron a la base de un gran árbol. Ella se sorprendió al ver que su casa era un árbol. El hombre la subió al árbol y pasó un día. La noche siguiente ella tenía hambre y le pidió comida al hombre. Corrió por el árbol y luego regresó con un cadáver de toro. Ella le dijo que la carne estaba cruda y que no la comería cruda. El hombre cortó un trozo y lo colocó sobre las luces de una ciudad lejana. Para él se parecía a un fuego. Estaba confundida y tan hambrienta que se lo comió. Pasó otro día y ella se quedó perpleja. Al tercer día se dio cuenta de que el hombre estaba extrañamente más peludo que de costumbre. Al cuarto día se dio cuenta de que el hombre era en realidad un oso. Poco después de que él fuera a buscar comida, ella se fue a toda prisa a su pueblo. Encontró a los aldeanos ya sus padres y les contó todo. Ella también les pidió que la escondieran y el oso regresará oliendo su olor. Efectivamente esa tarde el oso apareció en la entrada del pueblo. Todos los aldeanos se enfrentaron con el oso y un aldeano le cortó el estómago. El oso agarró la hierba alta y espesa y cosió su estómago antes de huir. La mujer y los aldeanos salieron victoriosos. Algún tiempo después, la mujer se encontraría embarazada y daría a luz a un oso con una fuerza enorme. Su nombre era Juan del Oso.”

A pesar de que solo hay una especie de oso en América del Sur (el oso de anteojos), la historia de La esposa y los hijos del oso es una historia destacada entre los pueblos andinos. Esta es la versión de Mami Panchas transmitida oralmente por su madre.